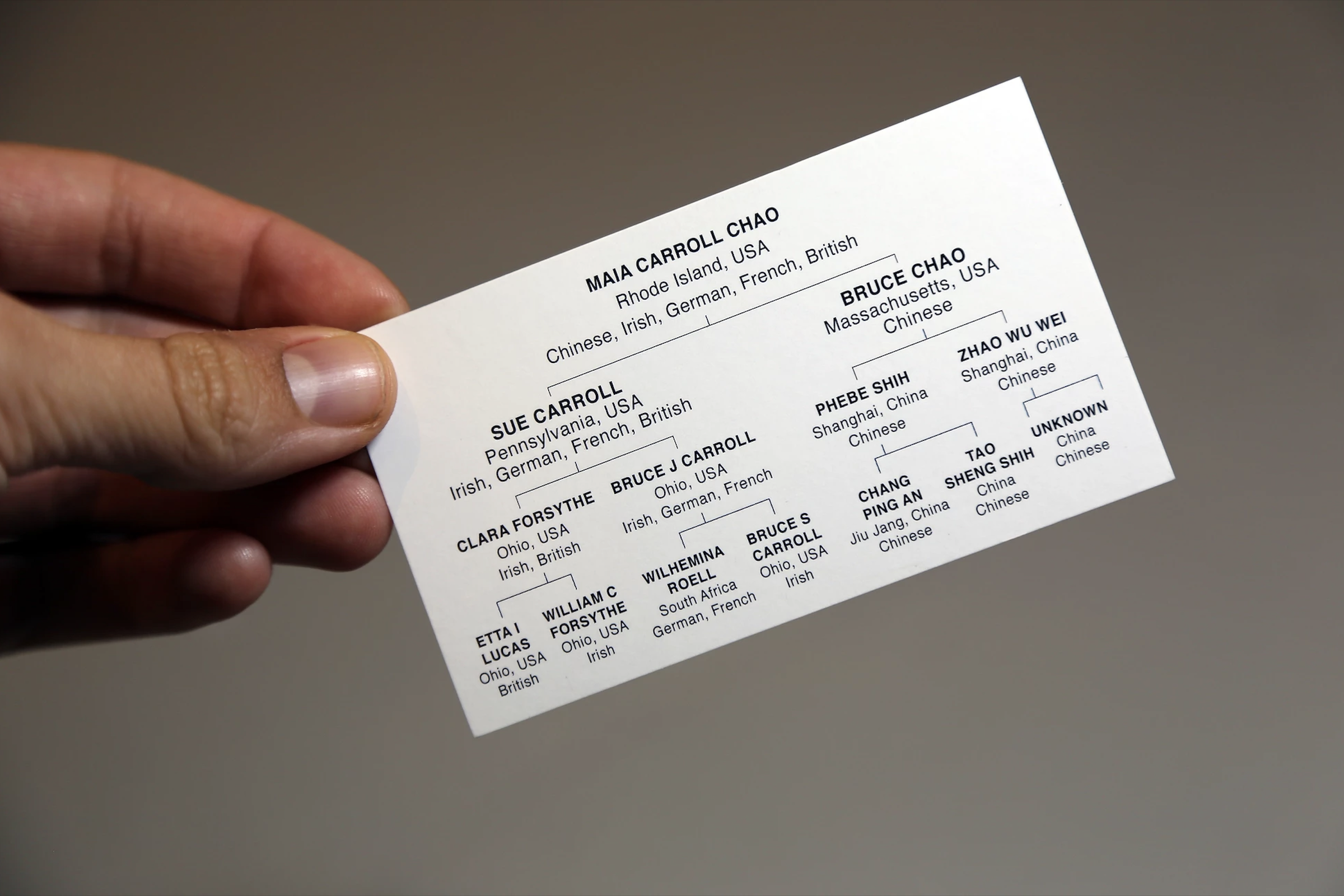

A native of Providence, Rhode Island, raised in a household of teaching artists, interdisciplinary artist Maia Chao’s first degree was in Anthropology from Brown University. When browsing the selected works on Chao’s website– business cards charting her genealogy, videos weighing the relationship between capitalism and depression– it’s easy to see the influence.

It was a desire to connect research with expression and play that led Chao to pursue a Master of Fine Arts (MFA) at The Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). Since, Chao has shown work at venues like The Shed and the RISD Museum, given talks at the ICA Philadelphia and National Art Education Convention, and has been written about in BOMB Magazine and The Paris Review. One of her most well-known artworks is Look at Art. Get Paid. (LAAGP), a program made with collaborator Josephine Devanbu that pays people who would not otherwise attend museums to visit as a guest critic- with the aim that their feedback would encourage institutions to examine their own lack-of-accessibility.

Currently, Chao is an artist-in-residence at Philly’s Recycled Artists in Residence (RAIR) and a member of the Vox Populi artist collective. Chao tells me that she “was drawn to Philadelphia because of its community-oriented, socially engaged art scene,” and because it “felt like a place where I could get that [9-10 hours] of sleep” per night. Coming soon: a film of performances from Chao and RAIR-collaborator Fred Schmidt-Arenales that “will attempt to forge a stronger connection between waste and everyday life.”

Morgan Nitz: As someone with a BFA who’s been asked countless times what can you do with that?, I’m always a little surprised when someone’s second degree– but not first– is in art. Can you tell me about your BA in anthropology, relationship to art, and what led you to RISD’s MFA program?

Maia Chao: The interests that drew me to cultural anthropology are very similar to the interests that drew me to art. I’m fascinated by people, sociality, and the systems and institutions we use to relate to one another. Studying cultural anthropology, critical ethnography, and qualitative research methods taught me a lot about knowledge politics, self reflexivity, and the ethics of working with people. But when I was studying anthropology I grew disillusioned by the prescribed methodology of ethnographic research and found myself at odds with the research ideal of objectivity. I was really curious about expanding the relationship between the researcher/subject and how to tap into more expressive registers like play and humor, so that’s what led me to art.

I’m interested in the fact that there’s a trend in some critical ethnography toward more expressive and experimental methods, and there’s also talk of the “ethnographic” turn in contemporary art… they’re converging!

MN: You raise a significant issue in your project Look at Art. Get Paid. (LAAGP): museums are not designed for, nor inviting to, the majority of the public– in particular, working class people, people of color, and people for whom English is not a first language. Can you briefly describe the project and then go into its impetus?

MC: I co-created Look at Art. Get Paid. (LAAGP), with my collaborator Josephine Devanbu. The social practice project pays people who don’t visit art museums to visit one as guest critics of the art and the institution. We started it as students at RISD, when we were grappling with the relevance of art to the greater public. We wanted to question the innate value of art and art institutions by reversing flows of money, power, and knowledge between the museum and the communities they neglect to serve. We considered our bureaucratic fluency and access to institutional money as artistic tools that we could use to create an equitable context for the labor of critique among first-time museum visitors.

MN: Was there a particular workshop, moment, statement from a participant, that affirmed what you and your team accomplished with LAAGP? Tell me that story.

MC: Critic Samanda Martínez said, “Están cuidando más a las imágenes que a nosotros/They’re taking better care of the paintings than they are of us.”

There were lots of useful comments that can be easily addressed by institutions. But for LAAGP the issue was not so much that institutions don’t know what to do to improve. It’s more of an issue of whether it’s a priority. A big part of how we saw our role as artists was to set up the conditions for honest feedback and to figure out how to make that feedback real, felt, and urgent to those in power. We made a video documentary about the project and presented that to the whole staff at the RISD Museum, and tracked subsequent changes at the Museum.

Though the project came to a close during the pandemic, I’m really excited that LAAGP’s model of paid, community-centered critique has informed and inspired similar programs at The University Museum of Contemporary Art at Amherst and even the Toledo Opera in Ohio. There are several institutions developing adaptations right now of LAAGP. That was always our hope—that this model could be adapted and used by institutions on their own. And it was recently discussed in Laura Raicovich’s book Culture Strike: Art and Museums in an Age of Protest (Verso Books, 2021), which is a really interesting survey of art and museums in this political moment.

MN: I love the way you use humor in your practice. There’s the silliness of reselling your parents their own items in works like Gently Used; the “funny cause it’s true” Studio Visit Intake Form; the darkly comedic Point of Purchase. Tell me how you approach art making and humor.

MC: I consider play, rehearsal, absurdity, and humor as integral operations of institutional critique. These qualities offer an inviting entry point to my art, but they’re also just a really important and organic part of my artistic process. I don’t set out to make funny things but I am really drawn to collaboration and spending time making with people I love. So humor and play naturally enters into those scenarios.

Recently, I learned the term “moral injury,” which refers to the emotional and spiritual harm that one experiences when participating in an act that transgresses their values. And this really resonated because I think that to be alive in this late capitalist era is to experience a continual state of moral injury. It can feel impossible to live, consume, and work without participating in interlocking systems of exploitation and oppression. I think in my art I tend to respond to a problem or experience of suffering, like competition or alienation. And, at the risk of being aggrandizing, I want to facilitate moments of repair or healing, and humor and play are such important tools for that.

MN: You’re a member of the artist collective Vox Populi. When did you join and what drew you to Vox? Are there any can’t-miss events upcoming at Vox?

MC: I joined Vox Populi basically a year ago and have really enjoyed being a part of such a longstanding artist collective in Philly. As an artist who has worked in the realm of institutional critique with larger, more formal organizations and institutions (read: very slow to change!), I’m really excited to channel my energy and research to a smaller, more self-reflexive and agile art organization, whose values I share and whose infrastructure is well-poised to support artistic experimentation, intervention, and institutional critique. In recent years, Vox has dedicated itself to centering the voices of QTBIPOC [Queer, Trans, Black, Indigenous, People of Color] artists and promoting the creative and political autonomy of underrepresented artists. And last summer Vox published a collective values statement. All of this kind of institutional transformation really excites me. I am deeply interested in how people self-organize and collaborate politically and artistically, ranging from the lofty (How do we define our values as a collective?) to the nitty gritty (How do we distribute labor for collective operations?).

MN: You and Fred Schmidt-Arenales, as a collaborative duo, are current artists-in-residence at RAIR (Recycled Artists In Residence). What are you working on? Can you share some spoilers?

MC: Yes, we have been spending a lot of time at the dump! We’re developing a film consisting of a series of performances that take place at the construction and demolition waste recycling facility. The project will attempt to forge a stronger connection between waste and everyday life. It will include observational footage, scripted and improvised spoken text, as well as music, dance, and song, all derived from materials pulled from the waste stream.

MN: What brought you to Philly from Providence, Rhode Island?

MC: After Providence I lived in NYC for a couple years. But I couldn’t handle NYC. I’m not the kind of person who can (or wants to?) work a full day and then go to the studio. I just don’t have that kind of energy. I need 9-10 hours of sleep a night! Philly felt like a place where I could get that kind of sleep. I was drawn to Philadelphia because of its community-oriented, socially engaged art scene. I appreciate that it’s financially possible for artists to run brick and mortar spaces and counter-institutions here, and that it feels like dominant art institutions have less of a stronghold on everything. It’s a place where it feels more possible for work/earning money to be a part of—not all of—how an artist spends their time and energy.

MN: Did you know about Philly’s reputation of being not-so-friendly before moving here? If so, do you think it holds up? Or were you pleasantly surprised?

MC: I guess? Being from the East Coast, I don’t feel much of a difference. I lived pretty close to Boston, and they’re known for being “mass-holes.” I have a lot of affection for Philly’s underdog, gritty reputation and pride. Did you hear about that hitchBOT—a hitchhiking robot that made it safely across Canada, Germany, and the Netherlands but then got destroyed in Philadelphia? I kind of love it.

MN: What do you think the Philly art community could do better or work harder on?

MC: I feel like I’m still getting a sense for the Philly art community, especially given the impact of the pandemic. I think there is always work to be done on inclusivity regarding race and class and what meaningful change looks like in art communities and organizations. But I’m building my understanding of Philly in particular. Generally, I’m freaked out by cancel culture in queer/art spaces! I’m listening to Conflict is Not Abuse right now…

MN: What are you excited about right now?

MC: This week I’m excited to film my gay choir (Philadelphia Voices of Pride) director singing opera at the dump! And I’m excited to start a new full-time teaching job that has health insurance. I didn’t think it was possible. I still can’t believe the reality of adjuncting…

This story is part of a partnership between The Philadelphia Citizen and Forman Arts Initiative to highlight creatives in every neighborhood in Philadelphia. It will run on both The Citizen and FAI’s websites.